Tuesday, December 7, 2010

Indie Author Guide Book Launch Twitter Giveaway - Winners!

I printed out all the tweets, cut them into individual slips of paper, shook 'em all up in a bag and drew the winners at random. Drumroll, please!

The winners of a signed copy of my book are:

@LenoxParker

@RDavisKeller

@ponilinda

@wildlypoetic

@ReDcirKle

...plus, I'm throwing in a bonus copy for @Mike_Gerrard, who was the first to tweet.

The winner of the one year, VIP subscription to Vault University is:

@1freddiehl

And the winner of the Kindle is:

@jmstro

Thanks once again to all who entered; I wish I could afford to give Kindles to all of you! To the winners: I'll tweet you with details about collecting your prizes.

Friday, December 3, 2010

Indie Author Guide Book Launch Twitter Giveaway - Win A Kindle, Vault U. VIP Subscription or Signed Copy of The Book!

- 1 one-year, VIP subscription to Publetariat Vault University, granting the winner access to all lessons in both the Publishing and Author Platform/Promo curricula - a $160 value

- 1 Wi-Fi Kindle - a $139 value

- 5 signed copies of The Indie Author Guide: Self-Publishing Strategies Anyone Can Use - $20 value each

Here's how to enter:

1) Anytime from now through midnight, PST on Monday, 12/6/10, tweet the following message, EXACTLY:

Check out #IndieAuthor Guide http://ht.ly/3jwgl great #selfpub how-tos/advice #iagwin (RT 2 enter 2 win a #Kindle! http://ht.ly/3jz7d)

You must tweet that message EXACTLY or I won't be able to find your contest entry(ies) for the drawing. You can tweet the message up to twice per day from today (12/3/10) through Monday, 12/6/10. If you have multiple Twitter accounts, you may tweet the above message twice per day from each account to increase your number of entries. Any tweets over the twice per day per Twitter account limit will be disqualified from the prize drawing.

Remember, duplicate tweets will tend to annoy your Twitter followers, so if you're going to tweet it twice per day, try to space those tweets out by at least six hours.

2) This part is optional, but for added karma points to help you win, go to the book's listing page on Amazon and scroll down to the "Tags Customers Associate With This Product" section (near the bottom, below the reviews and "What Do Customers Ultimately Buy After Viewing This Item" section); click on any of the tags with which you agree, and add any new ones you feel are applicable to the book

Winners will be chosen at random from all qualified tweets on Tuesday, December 7th. Watch for the announcement of winners here and on Twitter by 3pm PST on Wednesday, December 8th.

That's it! Good luck to everyone, and I'll see you back here next Wednesday.

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Ebook Madness: Don't Confuse Ebook Conversion With Ebook Formatting!

The conversion step is no big deal. You open a conversion program, click a button to import the (pre-formatted) manuscript, fill in a form with details about the book (e.g., title, author name, suggested retail price, etc.), click another button to add any required companion files to the project, then click one last button to output the ebook in your desired file format. If the manuscript file you've imported was formatted properly ahead of time, your ebook will look and perform great. If not, not.

The majority of time and effort that goes into creating an ebook is spent on preparing the manuscript for conversion, and creating any required companion files (e.g., Amazon's required active table of contents file for Kindle books). Where the conversion step is mostly automated, the formatting part is mostly manual. This is because every manuscript is different, and the process of formatting a manuscript for ebook publication is primarily a process of minimizing and standardizing formatting. Here's my Kindle book formatting to-do list, to give you some idea of what's involved:

* “Save As” to create Kindle file copy

* Insert cover image on first page

* Remove blank pages

* Remove headers

* Remove footers

* Set margins to 1” all around, remove gutter

* Replace section breaks with page breaks

* Set two carriage returns before each pg break and one after each

* Insert page breaks before each chapter heading, if necessary

* Replace double spaces with single space between sentences

* Standardize body text style

* Turn off auto-hyphenate (Tools > Language > Hyphenation)

* Remove any tab or space bar indents, replace w/ ruler indents as needed

* Set line spacing to 1.5, max 6pt spacing after paragraphs

* Standardize chapter headings

* Standardize section headings

* Remove/replace special characters

* Reformat graphics as needed to 300dpi resolution & optimal size (4x6” or smaller)

* Verify images are “in line” with text

* Insert page breaks before and after full-page images

* Modify copyright page to reflect Kindle edition verbiage

* Add correct ISBN to copyright page

* Insert hyperlinked TOC

I have a different to-do list for each different ebook format, since the requirements vary from one to the other. Obviously, if the author provides a file that already meets most of the requirements above, the job will take much less time and effort than it will with a file for which I must complete all of the items on my formatting checklist.

Just as obviously, it's impossible to know how much work is involved without actually seeing an excerpt from the manuscript. Anyone who's offering to do the job on the cheap without seeing any part of the manuscript is either not intending to do any formatting, or so new to the author services game that he doesn't realize the time and effort demands in creating ebooks are highly variable.

If you can find someone who will do the formatting AND the conversion for $50, and the resulting ebook looks great and functions properly, by all means HIRE HIM NOW! Otherwise, when you're comparison shopping among author service providers, be sure to ask if the price quoted for the provider's ebook conversion service includes formatting and creation of any required companion files.

Sunday, October 17, 2010

Write For All You're Worth

Today, I was disheartened and even a little sickened when this ad showed up:

Ghost writer needed to write 10 blog posts. Will pay $.01 per word for 200-250 word posts. You choose the topic. All 10 posts must be on the same topic. Topic must be legal and PG. Must be original posts - plagiarized posts will not be purchased. Looking for one writer. Long-term projects available for the right person.

Bring on the number crunching...

I think half an hour per post is a pretty realistic estimate of the time involved, if you count the time spent coming up with the concept, writing the rough draft, and editing and polishing. At a penny a word, the maximum-length blog post will net you---wait for it---two dollars and fifty cents. Write one more and you're rolling in five dollars an hour; that's about 40% less than minimum wage, and that's before taxes, too. You can't even argue that this is a resume builder, since it's a ghost writing job: someone else is going to take the credit for your work.

I think I just threw up in my mouth a little.

Look, I know tough times call for desperate measures, beggars can't be choosers, in times of crisis we all wear different hats, and lots of other cliches. But writing is a skill, writing well is a hard won skill, and even people who mop floors and flip burgers for a living are entitled to a minimum wage that's mandated by law. Yet although this gig will obviously pay less than either of those jobs would, the person who's hiring intends to be picky about selecting the "right person" for "long term projects".

The "right person" in this case is a fool who's willing to be taken gross advantage of, but I have no doubt he or she is out there, writing an eager email to apply for the job this very moment. And it's because of that writer that ALL of us, and our work, are being devalued faster than Detroit real estate.

Take a gig that pays minimum wage if you must, but do it knowing you're earning no more than you would working fast food or retail at the entry level---less if you play by the rules and take self-employment taxes into account. If you're good, you can and should command better pay. And "command" is exactly the right word for it.

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

ISBNs Don't Matter As Much As You Probably Think They Do, But You Might Want To Start Owning Your Own Anyway

In the case of an individual author who only self-publishes his own manuscripts (as opposed to someone running an imprint, publishing works by other authors) what does it matter, really, who's the registered owner of the ISBN on a book? There's no legal or regulatory tie between ISBN ownership/registration and copyright or intellectual property rights. ISBN registration only designates ownership of the ISBN, not ownership of the content of the book to which the ISBN has been assigned.

I've used Createspace's free ISBNs on all of my self-published books to date, and while this technically makes Createspace the 'publisher of record' in the ISBN records, I still retain all rights to the published material and I still own the copyrights. CS's terms of use state this explicitly, and CS is also very adamant that their company not be listed as Publisher on their clients' books' copyright pages.

ISBN ownership can help to establish the legitimacy of a publisher's claim to profits from a given book in a legal challenge situation, but given that CS has made it abundantly clear it never wants to be named as the publisher of record for any of the books it prints and distributes, the likelihood of CS trying to usurp my royalties seems pretty remote. Also, since copyright is the most meaningful measure of intellectual property ownership in the case of a book, and I own the copyrights on my books, the fact that CS is the registered owner of my books' ISBNs wouldn't allow CS to claim my intellectual property rights, either. One caveat: the financial and legal waters would be a bit murkier if I were running an imprint and publishing other authors' works as well as my own, and in that case I would absolutely want to purchase and register all the ISBNs in the name of my imprint.

While not being the registered ISBN owner prevents me from listing the books with wholesale catalogs myself, since Createspace now offers to create wholesale catalog listings as part of their service, it's a non-issue for me. My CS books are available on Amazon, Amazon UK, through Barnes and Noble, and through every other bookseller and retailer that stocks its inventory via the Ingram or Baker & Taylor catalogs, and that's most of them.

Borders is a special case, in that its online and in-store inventory is stocked from an internally-maintained catalog; the only way any publisher, indie or mainstream, gets her books listed with Borders is to get one of Borders' buyers to add them to Borders' internal catalog. Since my CS books are listed in the Ingram and Baker & Taylor catalogs, from which Borders draws entries for its internal catalog, I could approach a Borders buyer and inquire about getting my CS books added to Borders' catalog if I wanted to, but I haven't bothered.

True, my books aren't available through European wholesale book catalogs (since only the registered ISBN owner can list books with those catalogs), but since I'm not promoting my books in foreign markets nor releasing them in foreign language editions, I don't think I'm missing out on many sales there. Amazon UK is the #1 bookseller for English-language books in Europe, and my CS books are already listed on that site.

While not being the registered ISBN owner also prevents me from registering my books with the Library of Congress, I don't really care about that and I don't think anyone else does either---with respect to my books, anyway. It would matter if I were trying to get my self-pub books stocked by public and institutional libraries, but let's face it: self-pub books, novels especially, aren't likely to be stocked by those libraries anyway.

If I self-publish anything new in the future I'll most likely purchase my own ISBN/barcode blocks for the new projects, but only because "premium" or "expanded" distribution options offered by print and digital publishing service providers increasingly require that the author/imprint be the registered owner of the ISBN. Since this is already a requirement for Smashwords' premium ebook catalog, I expect it's going to become commonplace for ebooks to have ISBNs just like print books and hard media audiobooks.

Even so, I still see the whole thing as little more than an administrative hoop through which I'll soon be forced to jump and an extra expense I'll be forced to shoulder to make retailers' lives easier. Cost of doing business, and all that. I'm still not likely to list my self-published books with European wholesale catalogs, nor Borders' internal catalog, and I definitely won't bother registering them with the Library of Congress.

I have always maintained, and still maintain, that ISBNs are merely tracking numbers used by retailers, libraries and government agencies to organize, and retain control over, their inventory of books---nothing more, and nothing less. Some people (and I'm not talking about Joel Friedlander or anyone who's commented on his article) treat ISBN purchase and ownership like some kind of mark of legitimacy, and others even go so far as to tell self-publishers that if your book's ISBN isn't registered in your name, that fact alone makes your book a "vanity" project and you an amateur who doesn't deserve to wear the name "author".

Horsefeathers. There may be compelling business reasons for this or that indie author to purchase and register his own ISBNs, and there are definitely compelling business reasons for imprints to do so. But that's all they are: business reasons.

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Whither The Author-Artiste?

These are authors of seminal literature which has inspired whole generations of writers, thinkers and artists, and their works will continue to inspire thought and action for generations to come. Yet somehow I doubt any of them would've been very excited about, or done very well with, something as worldly and mundane as author platform. And this begs the question: where, and how, is the important and challenging literature of tomorrow to be discovered and brought to the public's attention? Will it be lost to the ages for want of a Twitter account and Amazon Rush?

I'm not saying the rise of indie authorship has somehow created this problem. If anything, indie authorship has opened a door of opportunity for those few authors of literary fiction and philosophical or metaphysical nonfiction who are also web savvy and/or highly motivated to get their work out to the world. After all, it's not as if mainstream presses have been clamoring for more edgy, unclassifiable, non-commercial manuscripts. Trade publishing in the United States hasn't been primarily about enlarging the canon of quality American literature for quite some time.

While there have always been passionate and compassionate editors, agents and others willing to champion this or that "great" book, regardless of its apparent commercial potential, these have increasingly been diminished to the role of mere voices in the wilderness. Because the publishing business is, first and foremost, a business, and there's nothing wrong, illegal, or unethical about that. A book that doesn't look like a substantial moneymaker isn't likely to be picked up by a big, mainstream house. Small, independent presses can bridge the gap between art and commerce to some extent, but those presses have to turn a profit to survive too. Great reviews and a slew of doctoral theses based on a given book won't pay the rent.

I've turned this over in my head again and again, but there are no easy answers. Plenty of people have gone through the exercise of sending some literary classic or other to a mainstream house or agent under a different title just to get it rejected and then knowingly blog about the generalized cluelessness of trade publishing (and in so doing, entirely overlook the fact that publishers are engaged in a for-profit business), but this exercise barely pays lip service to the larger issue. If we agree as a culture that important, if non-commercial, literature deserves wide exposure, study and discussion, who's supposed to foot the bill for getting it out there in front of eyeballs?

Indie authors like me who've worked long and hard to master platform and publishing skills may feel some righteous indignation at the notion of our artier, less business-savvy counterparts getting somewhat of a free ride when it comes to the labor involved in indie authorship, but we should try to get past this tit-for-tat mentality and look at the big picture. I know all kinds of things about self-publishing, trade publishing, setting up and maintaining an author platform, and the business side of indie authorship, and I'm a pretty good writer of entertaining little novels and instructional nonfiction, too. But I'm no Salinger, O'Connor, Dostoevsky, Garcia Marquez or Camus, and I never will be.

Is it better for the culture at large if the only new authors to achieve any meaningful level of exposure or acclaim are like me, succeeding largely for reasons having at least as much (if not more) to do with our business and marketing skills than our writerly gifts? I'm thinking, no. I have come up with some ideas to address the problem, but it's a woefully short list. Feel free to add your own suggestions in the comments area.

1. Introductory self-publishing, author platform and publishing business courses should be added to the core curriculum of all creative writing degree programs; many students in such programs may have no intention of ever self-publishing, but these subject areas are so commonplace in the publishing world of today that to be ignorant of them is indicative of an incomplete education.

2. The National Endowment for the Arts has grants on offer each year, but admittedly, they're limited to pretty specific categories and putting together an acceptable grant proposal is scarcely easier than setting up and maintaining an author blog and Twitter account.

3. Anyone who's mastered a crucial publishing or author platform skill like podcasting, ebook creation, book cover design or the like should share the wealth of those skills by providing some free instruction to their fellow writers in the form of how-to videos, articles, or podcasts.

4. Any author or publishing pro who's in a position to give wider exposure to a deserving non-commercial manuscript, book or story should do whatever they can to lend a hand to the writer in need.

Remember: it was probably some classic of literature, not a NY Times Bestseller, that originally inspired you to become a writer in the first place. Let's all do what we can to give that same gift of meaning and inspiration to future generations of writers, thinkers and artists everywhere.

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

When Redesigning Your Site Or Blog, Don't Forget To Grandfather

Some of the content on your site may be quite popular, with many links, tweets, backtracks and so on all over the web. Check your site statistics or pageviews to get a quick read on which pages or articles are getting the most traffic, check for backtracks/backlinks on any of your content (backtracks and backlinks are instances of other sites linking to yours) and also take a trip down memory lane to remind yourself which pages or articles you have heavily promoted in the past. Be particularly alert to any content that has been mentioned in the media or highlighted on others' websites and blogs.

When revamping your site or blog, be sure to keep that popular and much-linked content, and keep all of the associated web page addresses and links intact. After all, you've already put in the effort to create the content, and it's bringing new visitors to your site or blog on a regular basis. Why on Earth would you want to toss that valuable information and goodwill asset on the junk heap?

In the case of my old site, there was a very popular page containing a BookBuzzr widget which displayed the first edition of my book, The Indie Author Guide, online in its entirety for free, as well as a free guide to Kindle publishing. This page has received numerous positive mentions (with links) in the mainstream media. It was no cakewalk building my author platform up to a point where outlets like The New York Times, MSN Money, CNET and The Huffington Post were sending new site visitors my way, and the articles in which my guide had been mentioned will still be on the web for years, or even decades, to come. Even though that Kindle publishing guide is currently out of date and I'm in the process of updating it, and an updated and revised edition of The Indie Author Guide is on its way as well, it would've been a mistake to completely eliminate the page and leave a slew of broken links in the wake of my site redesign.

It so happens that I didn't intend to include this specific page in my new site. I'd created a new organizational scheme and the page just didn't fit. However, I didn't want to turn away any new visitors who might discover me through all those links to the page.

So I created a new version of the old page, to match the new site design, and ensured it had the same title and web address. I added a statement indicating I'm in the process of updating the guide and when I expect the new version to be posted, plus a statement with information about the revised and updated edition of The Indie Author Guide, so anyone landing on that page will get the most up to date information.

Note to those who actually write the code for their sites or blogs: even though the new page didn't have any need for HTML anchors to be included on it, I ensured all anchors present on the old page were included in the new one, so that any links pointing to those old anchors wouldn't be broken, either.

I didn't include this page in my site's navigation bar, because again, it just doesn't fit the new scheme. But anyone who clicks on one of those old links will not be disappointed, and since the navigation bar for my new site is on that "secret" page too, it's possible new visitors may click around a bit and learn more about me and my books.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

The 70 Per Cent Solution

No, I'm not talking about the 'delivery price' factor, which dictates the fee Amazon will hold back on your 70% royalty Kindle book based on the book's file size. Despite all the panic-mongering on that point, and all the worry about whether Amazon may choose to increase that fee at some point in the future, I think it's really no big deal. What I'm talking about is this little nugget from the terms of the 70% offer:

"Under this royalty option, books must be offered at or below price parity with competition, including physical book prices."

What this means is that if your book is being offered anywhere else, in any format, at a lower price than the price you've listed for your Kindle book on Amazon, Amazon will reduce your Kindle book's list price on Amazon to match the lowest price at which your book is being sold elsewhere. You'll still get your 70% royalty, but it will be on that lowest price. It's kind of hard to extrapolate all that from this one-liner in their terms, but I've learned it the hard way.

When I opted in for the 70% royalty and raised my Kindle book prices to $2.99 on Amazon to qualify for the program, I didn't remember my ebooks were being offered on Smashwords and Scribd in non-Kindle formats for $.99. I didn't realize my error until I was reviewing a sales report a couple of weeks later. So I immediately changed the prices on my Smashwords and Scribd editions to $2.99, and waited for Amazon to catch up. And waited. And waited some more, as every single day, I lost royalty money on every copy sold.

After a week I contacted DTP support, and it took another week to get their conclusive response: that my ebooks were still listed on Barnes and Noble's website at a price of $.99. See, B&N is among the expanded distribution resellers which carry Smashwords books when the author of the book in question has opted in for expanded distribution on the Smashwords site---which I had. Even though I changed the prices of my books on Smashwords, it can take weeks, many weeks, for those changes to propagate out to all the expanded distribution resellers. This isn't Smashwords' fault or doing, it's just the reality of waiting for outside companies to make database changes according to whatever processes they have in place. And like most things in mainstream publishing and bookselling, it's a very, very slow process.

So it actually would've been wiser for me to stay out of the 70% royalty option until after I'd raised my book prices outside Amazon and waited for those changes to propagate across all distribution channels. Since I didn't, all I can do is either stay with the 70% on a $.99 pricetag while I wait however long it takes for B&N to catch up, or change back to the 35% royalty option so Amazon will only base my royalties on my Amazon prices.

I chose the latter, but it's still going to cost me. You see, every time you change the price on your DTP Kindle book, or your royalty option, or pretty much anything else about it, you are forced to "re-publish" that book before your changes will be applied. Re-publishing makes the book unavailable for purchase for a minimum of two business days, and sometimes when you re-publish, the book gets stuck in a 'pending' status. When that happens you have to contact DTP support to resolve the issue, all of which means more days your book is not available for sale. When I re-published to opt in for the 70% royalty, my books all got stuck in the 'pending' status; one of them was unavailable for purchase on Amazon for seven calendar days.

Today I started that clock all over again, and I am again running the risk of my Kindle books getting stuck in 'pending' status---all just so I can get back to the 35% royalty option.

Now, don't misunderstand me. I am not saying this is all Amazon's fault, nor that any of it is Smashwords' or B&N's fault. All of my lost royalties in this are ultimately the result of my original oversight.

However, I DO think Amazon should be a little clearer about the full implications of their "price parity" policy, and the importance of matching your Kindle book's price across all resellers---including expanded distribution partners---before opting in for the 70% royalty. I also think the DTP should not require re-publication of a Kindle book when the author/publisher wants to make changes only to its price or royalty option. Why is it necessary to take the book off the virtual sales shelf for these things?

Here's hoping I don't get stuck in 'pending' again.

Sunday, July 11, 2010

A Good Edit Would've Fixed That

Mind you, I'm not talking about the occasional typo or missing space between words. Most of you would think those things are nits, just as likely to have been introduced in the typesetting phase as to have been overlooked in a prior editing pass, and I'd agree with you. No, I'm talking about a pervasive inattention to detail, improper usage or faulty constructions running throughout a given book's pages. Has your work fallen victim to any of the following problems?

Repetitive Usage - Do you have certain pet expressions or turns of phrase? It's fine to use them, but use them sparingly. In one of the books I've read this year, the phrase "that's the point" (and its many variants, such as "that's the whole point," "but the entire point of...", etc.) appears so frequently as to be distracting. Variations of the expression are spoken by every character in the book and turn up all too often: in one case, three times on a single page. On another page the phrase appears in two consecutive sentences, spoken by two different characters. Perhaps in that latter case, the author made a purposeful choice to be repetitive. If so, the desired effect isn't apparent.

Convoluted Sentence Structure - If I have to re-read many of your sentences or passages repeatedly to comprehend their meaning, your work fails the clarity test. This seems to be a particular bugaboo of fantasy and science fiction books. Perhaps in trying to achieve a certain tone of scientific realism or mythology, the authors simply go overboard with stilted language. Using big words, lots of technical, philosophical or religious jargon, or many made-up words doesn't automatically inject realism into your work. It's far more likely to introduce confusion. Also, as a rule of thumb, if you find a sentence you've written has more than two sub-clauses or phrases offset by commas, you probably need to think about breaking it up into multiple, smaller sentences.

Losing the Thread of Tense - If your character is recalling or retelling something that happened in the past, the recollection or retelling should generally be given in past tense---and stay in past tense. Consider this (totally fabricated) example:

I will always remember that summer. We went out on the boat nearly every day, and wished we'd never have to go back home. That year, my goal was to catch the biggest bass so I go to town one afternoon, I buy new bait and stronger fishing line. I get out on the water the next morning, earlier than anyone else. I cast my line and wait.

The first two sentences are in past tense, which is fine. The third sentence begins in past tense (goal was to catch the biggest bass) but then switches to present tense (I go to town, I buy new bait) and tense remains in the present for the rest of the passage.

Switching tense correctly is particularly important when the narrative is intended to go back and forth between past and present tense, such as when a detective is investigating a cold case and has to interview a bunch of people about their memories of the events in question. When tense changes, is the interviewee still talking about his past experience, or sharing some new realization with the detective in the present day? Tense is what's supposed to clue the reader in on this sort of thing, so if you're switching tense incorrectly or unintentionally, you're confusing the reader.

Using Internal Monologue for Omniscient Exposition - An internal monologue is nothing more than a character talking to him- or herself. We've all talked to ourselves at some point, we all know what it's like and how we "sound" in our heads when we're doing it.

We talk to ourselves to cogitate on things, refresh our memory of events, go over mental to-do lists and the like, but real-life internal monologues are not like journal entries. They do not provide a factual accounting of events, because the person experiencing the internal monologue already lived those events and knows what happened. They also cannot provide a factual accounting of events that were not witnessed personally by the individual having the internal monologue. Look at the following two examples---again, examples I've constructed just for this blog entry:

Mike couldn't stop obsessing over the events of that night. Three a.m., and his mind was still spinning.

Garrett refused to stop drinking, and I knew I shouldn't let him have his keys back, but I was afraid he'd shoot me if I didn't hand them over. He was doing about eighty when he hit that curve, still swigging from a bottle of Jack. He never knew what hit him. The funeral's tomorrow. I know what everyone there will be thinking, and they'll be right. It was all my fault.

Guilty or not, Mike knew he'd be expected to make a showing at the memorial service.

Compare this example to:

Mike couldn't stop obsessing over the events of that night. Three a.m., and his mind was still spinning.

What was I thinking?! I never should've given Garrett his keys, whether he was waving a gun in my face or not. Now he's dead and it's all my fault. How can I face everyone at the funeral tomorrow?

Guilty or not, Mike knew he'd be expected to make a showing at the memorial service.

In the first example, the author is using an internal monologue to present expository (factual or background) information from an omniscient point of view: the point of view of someone who knows, and can see, all that's happening or has happened to anyone involved in the story or setting, and also knows what any character is thinking or has thought at any given time.

The first monologue relates factual information Mike has no reason to be re-stating in his own head. It also reports on events which occurred outside Mike's presence; Mike might've learned how fast Garrett was going from a police report or news story, but how could he know Garrett was still swigging from a bottle when he hit the curve? And how could he know Garrett "never knew what hit him"?

The second monologue is more realistic. In it, Mike doesn't report on events, he reconsiders his role in them. He expresses his feelings about the events, and fearfully anticipates what's coming next.

This blog post is getting pretty long, so I'll wrap it up for today and report on some other common problems in a future post or posts. Bottom line: if my allotment of books from the contest gives an accurate indication, about 19 out of 20 self-published books need a professional edit---and aren't getting one. It's a real shame when a self-publishing author gets the tough stuff right (believable dialogue, pacing, plot, characterization) but releases a book that's still hopelessly marred by problems like those above---problems that could've been easily remedied by a good edit.

Monday, May 17, 2010

What's That?

Anyone who follows this blog knows that I'm not big on rules of writing. But in my experience as an author, a reader, and an editor, I've found that the word "that" is one of the least-needed, that it is among the most overused and misused words, in all of modern literature.

Notice how the "thats" add nothing to the passage. They don't clarify, they don't improve flow, and they don't reflect any sort of stylistic choice, either. They're just taking up space and bloating word count. The word "that" is only rarely actually needed in a sentence, but for some reason, an awful lot of writers are in the (bad) habit of peppering their prose with this largely superfluous word. Consider the following, typical constructions:

He knew that I wasn't going away.

vs.

He knew I wasn't going away.

She was sure that everything would be fine.

vs.

She was sure everything would be fine.

You get the idea. When you find yourself tempted to include a "that" in a sentence immediately following a verb or adjective, try the sentence without the "that" first. In the vast majority of cases, you'll find your meaning is perfectly clear, and your prose much tighter, without it. Now look at these constructions:

None of the cars that we saw were suitable.

vs.

None of the cars we saw were suitable.

The books that I needed weren't in stock.

vs.

The books I needed weren't in stock.

Again, the "that" adds nothing but characters on the page. As with "thats" following a verb or adjective, try any sentence where a "that" follows a noun without the "that", and see if it doesn't read tighter.

So when is it appropriate to use "that"? When it's needed to clarify your meaning:

As a pronoun - That is the hotel where we stayed last time we were here.

As an adjective - I'm pretty sure that book belongs to Jimmy.

Or to improve the flow of your prose, as a stylistic choice:

As an adverb - It didn't matter all that much.

(compare this to)

It didn't matter much.

The judge that heard the case was biased.

vs.

The judge who heard the case was biased.

All the kids that came to the party had a good time.

vs.

All the kids who came to the party had a good time.

Presumably, the judge is a person, not a thing. Kids are people, too. People are "whos", not "thats".

However, both of these examples illustrate the case where a relative clause requires an object to restrict an antecedent, which is just a fancy-pants grammarian way of saying a "that" or "who" really is needed to clarify the meaning of the sentence and make it grammatically correct. Just be sure to use "who" in reference to people, and "that" in reference to things.

One more thing: are you mixing up your "whiches" with your "thats"? Consider:

The dog that was found in her yard was a stray.

vs.

The dog, which was found in her yard, was a stray.

Note the difference in meaning. In the first sentence, the fact that (<-- see, even I think they're necessary sometimes!) the dog was found in her yard is an important detail. The use of "that" makes the subject, "dog", more specific. We're not talking about the dog she saw in the park, or the dog on the corner. In this type of usage, the phrase, "that was found in her yard" is called a "restrictive phrase".

In the second sentence, the fact that the dog was found in her yard is incidental. The sentence could be shortened to, "The dog was a stray," with no loss of meaning or clarity. In this type of usage, the phrase, "which was in her yard," is called a "nonrestrictive phrase". The phrase does not exist to better specify a particular dog, it's there to provide additional information about the dog.

It can be a tricky distinction. Let the comma be your guide when choosing between the two words. In general, if the desired meaning or emphasis of a given sentence is best conveyed when a descriptive phrase within it is offset by commas, you're looking at a nonrestrictive phrase and "which" is the right way to go. Conversely, if such a phrase is not surrounded by commas, you're looking at a restrictive use and can safely go with "that".

Also note, what's grammatically correct isn't always a match with the most commonly-accepted usage:

The puzzle pieces which we couldn't find this morning turned up under the cushions.

Gah! This sentence is like fingernails on a chalkboard to a grammarian's ears because it uses "which" as part of a restrictive phrase. Yet the sentence will seem correct to most readers because most of them think the rule used to divide the "thats" from the "whiches" is based on whether or not the noun in the sentence is plural. Look at the grammatically correct version of the same sentence:

The puzzle pieces that we couldn't find this morning turned up under the cushions.

It sorta kinda doesn't "sound" right, does it? It's because the incorrect usage has become more ubiquitous than the correct one. You can moan and complain, stamp your little grammarian feet, and even threaten to pull out your Chicago Manual of Style, but about 99 times out of a hundred you will lose a bar bet on this. It's usually fine to go with the more common, incorrect usage in such a case, but better still to avoid the whole kerfuffle and dispense with both words whenever possible. Remember, most often, you'll find a given sentence is just fine without either one:

The puzzle pieces we couldn't find this morning turned up under the cushions.

But if you should find yourself in a bar with nothing better than grammar to bet on, whip out your web-enabled phone and bask in the victory round - Grammar Girl's got your back.

Sunday, May 2, 2010

When Editing & Critiquing, Check Your Personal Opinions At The Door

I've been on the receiving end of revisionist edits and notes which were based entirely in matters of the reader's personal sensibilities, and it's an experience that's annoying at best, downright offensive at worst. Imagine having your independent, feminist protagonist watered down by a reader who feels such traits are unattractive in a woman. Or getting the note that there are too many references to liquor and bars from a reader who happens to be a recovering alcoholic. Such notes aren't helpful, because while they demonstrate very clearly how to alter the manuscript to better suit one specific reader's tastes, they don't offer any guidance on how to improve the manuscript in a way that will make it more appealing to the general public.

Editing and critiquing demand judgment calls from the reader, but it's a very narrow kind of judgment which should be based only in matters of linguistics and literary form. For example, it's fine to suggest the author eliminate a lengthy passage of navel-gazing on the part of the indecisive protagonist because it brings the story's pace to a crawl, but it's not okay for the editor to make the same suggestion merely because she has no tolerance for indecisive people in real life.

It can be a very fine line to walk, because the nattering observations of an indecisive person truly will seem to bring the story to a crawl for a reader with no patience for such people. But it doesn't mean a reader who doesn't share that particular pet peeve would suggest the same change. This is one of the many reasons why authors should seek out multiple reads from different people, and one of the many reasons why those readers should approach their task with self-awareness and humility.

In the end, matters not specifically pertaining to rules of grammar, spelling and proper usage are all matters of opinion, and this is something authors, editors and critiquers alike should never forget. What one reader finds distasteful, another will find fascinating. What one finds boring, another will find lyrical.

For authors, the trick is to work toward some kind of majority consensus. For editors and critiquers, the trick is to remember that their proper role is merely to bring the author's vision of his ideal manuscript into sharper focus, not to alter it, editorialize on it, or make it more closely resemble whatever vision the editor or critiquer may have in his own life or philosophy.

So, while I may not agree with an author who says [insert viewpoint to which you are strongly opposed here], it's still my job as editor to ensure his message is communicated as clearly and forcefully as possible. If I've done my job well, by the time I'm finished I will have helped the author win some converts to his cause---just as I've been won over to various causes by well-written treatises. And if I have a problem with that, I shouldn't be editing his manuscript in the first place.

Sunday, March 28, 2010

Writing Can Save Your Life; Let It

The blog of record for what I'm going through is To Hell & (Hopefully) Back. I won't be writing about any of it here, because this is a blog about indie authorship, not coping with trauma.

Still, there's one aspect of it that's worth addressing on this blog. As I endure, and one day come to embrace, the changes being thrust upon me, writing will be a key survival tool.

Finishing my revisions to The Indie Author Guide and then working with my editor to get the book ready for print will provide me with the much-needed distraction of work, and remind me that I still have something to contribute in the world.

Blogging at To Hell & (Hopefully) Back will help me acquire and strengthen the discipline and self-control that will be demanded of me in the coming months and years, to articulate my feelings and share my experiences in a constructive way, and hone what may be my most valuable survival tool: my sense of humor. It will help foster the habit in me of thinking about these difficult times as a necessary, if painful, transitional period that will end someday, and from which I can learn and grow.

Pouring my anger and pain into letters that will never be sent will offer an outlet for all the negativity that has to come out, but has nowhere to go.

Getting back to work on my author platform in preparation for the release of my book in November will keep me connected to the part of my community that exists apart from what's happening in my personal life, which will keep me looking to future possibilities instead of dwelling on past injuries. It'll give me a place to be the me who's capable and productive.

The marketing push I'll need to engineer when the book comes out will offer me a welcome diversion during what's sure to be the most difficult holiday season of my life.

If you're a writer, count yourself lucky. You have a crisis survival utility belt that rivals anything the caped crusader's got.

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

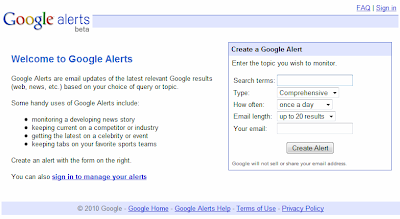

You Need Google Alerts

How To Use Google Alerts

The way it works is simple: you go to the Google Alerts page and set up a separate Alert for each word or phrase you'd like reported back to you. Note that you don't have to have a Google or Gmail account to do this.

What Alerts Should Authors Have?

I recommend authors set up alerts for their author or pen name(s), the titles of each of their books, the name(s) of their blog(s) and/or website(s), and the names of any events, sites, etc. with which the author is affiliated. I also recommend the following settings for Alerts:

Type: Comprehensive - so you don't miss any mentions

How Often: once a day or once a week - so you're not inundated with Alert emails

Email Length: up to 20 results - this limit will probably far exceed the actual number of results in your Alerts for a very long time

Be sure to enter your Alert search terms the same as you would in a search engine. Use quotation marks around phrases and full names to avoid a lot of incorrect results. For example, if I entered the Alert search for Publetariat's Author Workshop Cruise like this:

Author Workshop Cruise

my Alert would include any references to "Author", "Workshop", or "Cruise". If I enter the search term like this:

"Author Workshop Cruise"

my Alert will only include references to the entire phrase, "Author Workshop Cruise".

Alerts based on general search terms will return a lot of false positives even when you employ quotation marks, but it can't be helped in some cases. For example, I've set up an Alert for ' "Snow Ball" + novel ' to be notified anytime my novel Snow Ball is being bandied about online, but I also get a lot of hits from people who are talking about about actual balls of snow. Still, I'd rather scan through a few false positives each day than stay in the dark about it when people are talking about my book.

Only people with Google/Gmail accounts can make changes to their existing Alerts, and this is accomplished via the "Manage Alerts" link in any alert email. Users without Google/Gmail accounts can only delete existing Alerts and add new ones. If you don't have a Google/Gmail account and you need to change one of your Alerts, here's how to do it:

1. Copy down the parameters of the Alert from within one of its Alert emails, and mark the email with a star or file it in a location where you can easily locate it later

2. Go to the Google Alerts page and create a new Alert, using as many of the parameters you copied as you wish, and changing any you need to change

3. After you've received an Alert from the newly-created version (so you know it's working), return to the Alert email from which you copied the parameters, and click the "Delete this alert" link

How To React To An Alert

When an Alert notifies you of a positive mention, go to the site and see if comments are enabled. If they are, leave a note of thanks to the post's author, along with any additional remarks you can offer about the article, discussion topic, or post in question. Be sure to check off the "be notified of any responses" box, if there is one, so if anyone replies to your comment you'll be notified and can come back to respond. Also be sure to spread the word by sharing a link to the page whenever appropriate. This is a win-win that rewards the person who mentioned you or your work by driving traffic to their site, and strengthens your author platform by demonstrating that people are saying nice things about you or your work.

You will be amazed at what a big impact your response and publicity can have on the people who've mentioned you or your work. They will feel validated and appreciated, and will be that much more likely to sing your praises whenever the opportunity arises.

When an Alert notifies you of a negative mention, you'll need to decide whether or not it will be productive for you to respond. In most cases, it isn't. Please see these posts for additional guidance:

Congratulations, You Get To Be The Bigger Person Now

Internet Defamation, Author Platform, And You

So head on over to Google Alerts and get your personal tattle-tale on the job right away!

Monday, February 8, 2010

Avast Ye Lubbers, And Hear Ye Me Pirate Tale of Two Clicks!

May has been waiting for two specific, favorite old music tracks to become available for sale in digital format for many years. Both songs are from British artists, and the albums on which the tracks were originally included have been out of production for years. Kind of like a book the publisher has allowed to go out of print.

May started by checking iTunes, Amazon’s mp3 store, eMusic, and every other legitimate digital music vendor site she knows of to see if the tracks were available for sale. They weren’t, so she used each site’s contact form to request them. Months and years passed, and the tracks remained unavailable on vendor sites.

So she did periodic internet searches, just in case some new vendor might show up with the tracks on offer. She also checked the artists’ websites for any updated information from time to time. Every time she did these things, she’d spend half an hour or more on the necessary research; she really wanted those tracks, and she wanted to get them legitimately. And every time, she’d come up empty-handed. Except for the many links to pirated mp3s of the files she wanted, of course.

Those links were always there, right at the top of any search results, putting the tracks tantalizingly close. And sometimes, she’d follow one of those links to see if the tracks were really there, in their entirety, and in a high-quality file. They were. And on most of the web pages she found, the tracks were downloadable with a simple right-click/Download As command combo. No need to be a semi-hacker, or subscribe to a bit torrent service, or sign herself up for a file sharing network. Just two mouseclicks, and she’d have those songs she’s wanted so badly for so long. But every time she went on this reconnaissance mission, she’d resist the temptation of those two mouseclicks. Until this past weekend, that is.

This past weekend, she decided she was finished wasting her time and energy on the search. In frustration, she joined the ranks of the many consumers who eventually come to feel it’s the publisher’s or producer’s own fault if she downloads pirated copies, because they failed to offer her a reasonable, legal alternative.

She might’ve gone to a reseller site, like eBay, to purchase the CDs upon which the desired tracks originally appeared, this is true. But is it reasonable to expect her to spend somewhere around $10 each for the CDs, plus shipping costs, when she only wanted one track off of each? And while it may be a simple case of guilty rationalization, was she wrong to conclude that since purchasing a used copy would not benefit the artists or producers of the tracks, doing so was no better for the artists and producers than downloading pirated copies?

Now, imagine if May had been on the hunt for an ebook instead of these two music tracks. Imagine further that the book in question is out of print—though not yet in the public domain—, and neither the publisher nor the author has elected to make it available in electronic formats. May could purchase a used copy of the book from any of a number of resellers, but this won’t put any additional royalties in the author’s pocket, or send any money the publisher’s way. And May really prefers ebooks to hard copy books; she’s bought a Kindle or Sony Reader, and intends to make the most of her investment by limiting her book purchases to e whenever possible. If you were in May’s place and found yourself two clicks away from obtaining the desired book in e format, what reason would you have to resist those two clicks? What reason has the publisher or author (in a case where rights have reverted) given you to resist those two clicks?

Taking this a step further, let’s imagine the book in question is still in print, but only in a hardcover edition. May faces the choice between paying $25-30 for a ‘dead trees’ version, or two mouse clicks to get the book in the format she wants for free. May doesn’t want to cheat the publisher or author out of their due, but she can’t afford to spend that much money on a book. So she simply crosses that book off her wishlist, and while she has every intention of keeping an eye out for an electronic edition, life goes on and in a matter of days she’s forgotten all about the book. In the end, she never buys a copy at all.

In yet another scenario, imagine the ebook is made available, but only at a pricetag of $14.99, and with DRM that will prevent May from moving the ebook among her various devices. Furthermore, if May “purchases” the $14.99 ebook, she won’t really own a copy of the book at all. She’ll own a limited license to view the book’s content on one specific device, only in the format specified by the publisher, and that license is subject to recall under numerous circumstances. If the publisher becomes aware of any copyright irregularities, or if May gets into a dispute with the ebook vendor site on an unrelated matter, for example. Alternatively, she can buy the paperback for $13.99 and have a physical copy that she keeps in perpetuity, or can lend to others, or resell when she’s finished with it.

Or she can click her mouse two times and get the ecopy she wants, with DRM stripped, for free. Could you blame her for feeling the publishers’ excessive pricing and limitations on the ebook edition justify a decision to go the two-clicks route?

Observe and learn: this is how well-meaning, otherwise honest consumers are lured—some might say pushed—into piracy. Most consumers want to do the right thing. They want authors to be rewarded for their hard work. They want publishers to earn a fair profit on their products. But they also want reasonable prices, and the same flexibility and functionality they’d get with a hard copy book.

Publishers and authors who think raising the prices and restrictions on ebooks will work because readers will have no other choice are forgetting about those two mouseclicks. And the many justifications they’re giving consumers for making those two mouseclicks.

No publisher or author would have much to worry about with respect to ebook piracy if they would just give readers what they want, within reason. The criminal element that cares nothing for compensating content creators is a small group that will always find a way to steal content no matter what you do. But that group’s ranks are being joined by guilty, reluctant ‘pirates’ every day. This new type of pirate isn’t out to hurt authors, and in fact would probably be very happy to “pay” a reasonable price for pirated copies through the use of a donation button on authors’ websites. But of course, this would still be illegal and would likely put the author in hot water with his or her publisher.

Publishers: other than complaining about how wrong and unfair it is, what are you doing to make a legitimate, legal option both available, and more attractive, to consumers than a free ebook that’s just two clicks away? Because at the point where your choices with respect to ebook pricing and restrictions look more unethical to the consumer than their own choice to download a free, pirated copy does, you’ve lost the sale.

And Authors: if the only thing standing between you and giving your readers what they want is a publisher, have you considered the possibility of retaining your e-rights and releasing ebook editions of your work yourself? I’ve provided a free guide for publishing to the Kindle on my website, and there are many for-hire services that can do it for you. This is impossible for works already under contract, but is it a move that might make a whole lot of sense for your unpublished works, or works for which rights have reverted back to you?

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Amazon v. Macmillan: Authors, Are You Backing The Right Horse?

[Earlier this week], Amazon announced it will cave to Macmillan’s demand that it sell Macmillan Kindle books at up to $14.99 instead of the $9.99 pricetag that’s become standard for Kindle bestsellers. Per a report on Booksquare, Macmillan may have plans to price their Kindle books across a range, anywhere from $4.99-$14.99, and author royalties on those books may be based on an 'agency model' calculation which computes author royalty as a percentage of net, not a percentage of list price. See the linked Booksquare post for more information.

Macmillan authors are rejoicing, and I’m shaking my head.

Would musicians cheer a decision on the part of their labels to raise the price of their music on iTunes by up to 43%? I think not. Yet despite the fact that their books may cost up to 43% more than other Kindle bestsellers, and their royalty on those sales won’t be even one cent higher, the Macmillan author “victory” dance continues apace on the interwebz. The Author's Guild has come out on Macmillan's side too, and I'm completely mystified by that stance since Macmillan's change in terms with Amazon only stands to hurt authors and ebook readers alike.

The only reason I can think of for authors to be on the wrong side of this battle is that they don’t understand it. Let’s look at the facts.

1. Under pre-existing terms Amazon pays big publishers like Macmillan half the hardcover price on each Kindle book they sell: generally, that’s between $12-$17. This means Amazon is taking a loss on the sale of every such Kindle book, but the publisher is still getting its standard share, regardless.

2. Macmillan cut their standard author royalty on ebooks from 25% of the list price to 20% of the list price last October.

3. Amazon announced last week it will grant a royalty of 70% of the list price to U.S. authors and 75% to UK authors who sign Kindle book publication deals with Amazon directly. Ian McEwan, Martin Amis and Stephen Covey are just a few of the authors who’ve already signed on. A data storage/transfer/processing fee of .15 per MB will be deducted from list price prior to the 70% royalty split's calculation, but Amazon states that on average this fee only amounts to .06 per Kindle book sold.

4. The author’s royalty in either case is/was based on the list price of a given book, not the price at which the book is/was ultimately sold. This means Macmillan authors used to get the same royalty on every sale whether the customer paid $14.99 for it, or $9.99 due to Amazon discounts.

5. Last week Macmillan informed Amazon that if Amazon wanted to continue to sell Macmillan books in Kindle format, Amazon would have to raise [or lower] the prices on them to Macmillan's stated prices. If not, Macmillan wanted Amazon to delay release of new Kindle books by 7 months following a hardcover release, and, according to this report, several months following release in Apple's iBook store.

Recent reports have said Macmillan asked Amazon to match the 'agency model' deal it made with Apple's iBook store, which dictates a 30/70 split (70% going to the publisher) and allows the publisher to set the price at which each ebook would be sold. If Amazon did not agree to these terms, Macmillan would allow Amazon to continue to sell Kindle editions of their books under existing terms, but wouldn't allow Amazon to release the Kindle edition of a new book for sale until 7 months after its initial release in hardcover and several months following release in Apple's iBook store. I have yet to hear or read any report as to whether these delays would also hold for books intially released in trade paperback or mass-market paperback editions.

6. Amazon didn’t agree to Macmillan’s terms, and childishly removed the Amazon ‘buy’ links for all Macmillan books from its site in response to Macmillan's demand for new terms.

7. Macmillan authors stormed the internet, posting angry diatribes against Amazon and drumming up support among their fans and followers for Kindle and Amazon boycotts. Yes, that’s right: they took the side of the party who demanded that Amazon raise the price of their Kindle books, or delay their release by 7 months, or reduce the price of their ebooks below Amazon's $9.99 standard and pay their royalties based on an agency (net profit) model instead of the percentage-of-list-price model they've had on their Kindle books to date.

It was Macmillan which set forces in motion that ultimately resulted in the removal of ‘buy’ links, not Amazon, and while Amazon's actions in this seem excessive, I still see plenty of reasons for authors to be irked with Macmillan. If the report stating that Macmillan intended to withold Kindle editions of their books for a number of months after those books were released in the iBook store is true, is that a move that would've pleased the thousands of readers who own a Kindle, or who use the Kindle reader app on their computers or portable devices? Seems like a rather diabolical move to pressure ebook consumers to buy their ebooks from Apple (at higher prices) instead of Amazon, no? And isn't it very likely that by the time Macmillan books were released in the Kindle store following this Macmillan-imposed delay, Kindle-reading consumers would have forgotten all about those titles and moved on to other, more readily-available ebooks?

I don't own a Kindle, but release delays and pricing impact my book-buying decisions, too. I rarely buy hardcovers because they're so expensive, and there's many a book I intended to buy if/when it came out in softcover or e or audio, but either the book was never released in those formats or---salient in this case---by time it did, I'd forgotten all about it. This same phenomenon among ebook fans is well-documented, and ebook fans have always clamored to have their preferred format released at the same time as any print edition.

Also, recall that Macmillan may be planning to offer Kindle titles in a range from $4.99-$14.99. This isn't good news for their authors either, since Kindle books priced higher than $9.99 will be a tough sell and those priced below $9.99 will net the author a lower royalty. None of Macmillan's intended changes in its Kindle books deal with Amazon stand to benefit Macmillan authors or ebook readers. The intended changes only stand either scare off sales (in the case of Kindle books priced higher than $9.99 or those delayed by 7 months) or reduce author royalties (on Kindle books priced lower than $9.99).

So while I can understand Macmillan authors' anger at Amazon for having their buy links removed, especially in the case of authors of books offered in print editions only (since they don't even have a horse in this race), I still don't understand why Macmillan authors haven't been publicly objecting to Macmillan's actions as well. Macmillan presented Amazon with an ultimatum in which either option hurts authors' and ebook readers' current situation.

8. Macmillan authors will not receive one penny more in royalties on their Kindle books if those books are priced up to 43% higher, because their royalties were always based on the list price for their books, not the price at which Amazon ultimately sold them, in the pre-existing arrangement. Now their royalties will be based on 70% of the ebook retail price, and it’s a safe bet their books will be netting fewer sales if prices go up to $12.99-$14.99.

9. The upshot is a lose-lose-lose. Consumers lose reasonably-priced Macmillan Kindle books, and reasonably-priced Apple iBooks too, since according to this NY Times article:

With Apple, under a formula that tethers the maximum e-book price to the print price on the same book, publishers will be able to charge $12.99 to $14.99 for most general fiction and nonfiction titles — higher than the common $9.99 price that Amazon had effectively set for new releases and best sellers. Apple will keep 30 percent of each sale, and publishers will take 70 percent.

So Macmillan earns the dubious distinction of being the first major publisher to make calculated moves to drive ebook prices higher across all platforms. Thanks to Macmillan's "victory" over Amazon, Macmillan, authors and Amazon all stand to lose sales. Macmillan stands to lose market share. Authors stand to lose readership.

10. Prediction: emboldened by Macmillan’s so-called win, other major publishers will likely follow suit. More “lose” for everyone.

So tell me again: exactly why, and what, are we supposed to be celebrating here? I can already imagine the one objection I hear raised in discussions on this topic again and again: Macmillan is staving off devaluation of the ebook. There’s much hand-wringing over the notions that authors can’t possibly earn their due on low-priced ebooks, and that authors (like me) who sell their ebooks at prices significantly lower than the $9.99 Kindle store standard are somehow doing a great disservice to our fellow authors and trade publishing overall. This is so patently untrue, and such a pointless distraction from more important ebook issues, as to call to mind the Chewbacca Defense.

Under the pre-existing deal between Amazon and Macmillan, Macmillan authors earn a royalty of about $3.19 on their Kindle store standard-bestseller-priced books, whether those books are sold at $9.99 or $15.99. Under the new deal, which is the same in both Apple's iBook store and the Kindle store, authors would earn a royalty of just $2.10 on an ebook priced at $14.99: 20% of 70% of the book's $14.99 list price, and about $1 less in royalties per copy sold than what they have earned on their standard-priced Kindle books to date.

At a 70% royalty, I can earn $3.50 per copy sold of my self-published Kindle novels if I price them at just $4.99. The higher retail price does not add value for the author or the consumer, and at this point, it doesn’t even increase Macmillan’s profit since they’ve always gotten half the hardcover price on all their Kindle books from Amazon.

It's quite clear that Macmillan's take on each Kindle book sale under the new deal will be less than what they've received to date on those sales (since they used to get 1/2 the hardcover price and will now only get 70% of the ebook list price, which appears to have an upper limit of $14.99 for the foreseeable future), but I guess they decided they were willing to take that financial hit in exchange for the freedom to set their own ebook retail prices. Of course, Macmillan was under no legal obligation to include authors in their decision-making process, even though their decision stands to reduce their authors' Kindle book royalties by up to 33%; I'm just saying it's mind-boggling to me that Macmillan authors don't seem to be the least bit peeved at this outcome. In fact, they don't seem to have noticed it at all.

Publishers claim they need to wrest pricing control back from Amazon for the sake of what Amazon might do someday if it becomes too dominant in the ebook space. What if Amazon eventually decides to tell publishers it will no longer pay them half the hardcover price for their Kindle books, for example?

First of all, that’s a bridge to be crossed if, and when, someday arrives. Second, perhaps the correct answer in the event of that scenario is for publishers to lower their wholesale ebook prices. They claim it costs them just as much—or nearly so—to bring an ebook to market as it does to bring a hard copy, and they are therefore justified in their current pricing demands. But if it really takes a small platoon of publishing professionals and tens of thousands of dollars to bring a Kindle book to market, how is it possible that authors like me, JA Konrath, Piers Anthony, and countless others are doing it by ourselves, in our homes, from our consumer-grade computers, in a matter of hours?

“Your Kindle books lack the professional layout and design a publisher can bring to their Kindle books,” some of you are no doubt answering. This is true. But the thousands of readers who buy Kindle books from me, Konrath and the many other self-publishing Kindle book authors don’t seem to care all that much. I suspect that if you asked them, they would tell you they’d rather have a minimally-formatted Kindle book that costs $4.99 (or less) than an exquisitely-formatted Kindle book that costs $14.99.

As I’ve stated before, publishers arguing in favor of higher priced ebooks are ignoring the customer’s priorities in favor of their own, self-imposed priorities. This is because the ugly truth is this: the only parties being hurt by low-priced ebooks are big, mainstream publishers. Their overheads cannot be sustained by $4.99 ebooks, but that doesn’t mean their costs to bring ebooks to market should be forcibly subsidized by authors or consumers. To quote Konrath, “It would have really sucked to have been a buggy whip manufacturer when Henry Ford introduced the Model T. But technology changes things, and it isn't always fair.”

In the end, all the arguments I’ve heard and read about the devaluation of the ebook are toothless. There seems to be this notion floating around that books must be expensive in order to inspire readers to value literature, but that’s ridiculous. If I’m earning more on my $4.99 Kindle books than a Macmillan author earns on a $15.99 Kindle book, both on a per-sale and volume basis, how is my book’s low pricetag hurting me, the author? And if low-priced ebooks bring more literature and ereaders within reach of more consumers, how are the books’ low prices hurting literature and literacy? If anything, low-priced ebooks stand to benefit authors and consumers alike, and advance the cause of literacy overall.

Hasn’t it been wonderful to find short fiction and poetry collections—species on the verge of extinction in trade publishing—coming back into their own in the Kindle store? It seems readers are only too happy to take a chance on these supposedly ‘fringe’ books if the price is reasonable. Midlist authors are earning new royalties and new readers by bringing their backlists back into print on the Kindle as well. Most importantly, in my view anyway, the current indie author movement wouldn’t be possible at all without Amazon’s equal treatment of indie and mainstream authors.

So authors, indie authors especially: if you’re backing Macmillan in this flap, why? Has Amazon's overreaction distracted your attention from the long term ramifications of Macmillan's move, and the likely damage to be done to you and your readership? To put it another way, see if you can answer this question: what part, if any, of Macmillan's revised agreement with Amazon stands to benefit you?

Friday, January 29, 2010

Why I See The iPad As An Epic Ereader Fail